Between 2014 and 2022, the Brennan Center and Verified Voting released a series of analyses detailing the problem of aging voting equipment in the United States. These analyses rely on data provided by Verified Voting, which has been tracking voting equipment usage since 2006. This update examines the state of the nation’s voting systems ahead of the November 2024 elections.

When we first reviewed the status of voting equipment nearly a decade ago, we found that almost a quarter of all Election Day voters in 2016 would cast their votes on machines that did not produce a paper backup of their vote. Election experts consider a paper backup to be a critical security measure to ensure that ballots are counted as the voter intended. By 2024, that number has dropped dramatically, with only three states likely to still use paperless voting equipment in 2024. Indeed, we estimate that in the upcoming presidential election, nearly 99 percent of all registered voters will live in jurisdictions where they can cast a ballot with a paper record of the vote, including 100 percent of voters who will cast ballots in battleground states.

Much of the progress that has been made since 2016 is due to an influx of federal funds for election security. In 2017, in the wake of unprecedented cyber threats to elections, the Department of Homeland Security designated election equipment as critical infrastructure. After this designation, Congress provided $380 million in 2018 to help states acquire secure election technology, followed by another $425 million in 2020. Since the 2020 election, Congress has continued to provide election security grants, but in far lower amounts — just $75 million in both 2022 and 2023. This federal funding is the first of its kind since 2010 and helped make it possible for many states to replace outdated equipment.

But upgrading voting technology is a continuous process. Like any type of electronic equipment, voting machines age and need to be upgraded, and continued funding for elections makes this possible.

Small technical failures with voting equipment can lead to viral misinformation about the trustworthiness in elections. While minor errors and disruptions in elections do sometimes occur, election officials have numerous checks and processes in place to help make sure any issues are caught and addressed. And federal and state authorities should do all they can to support election officials in minimizing such errors. Election administration itself has been under a microscope in recent years, with domestic and foreign actors looking to exploit any problem for the purpose of undermining confidence in the entire democratic system. Jurisdictions can reduce the likelihood of disruptions on Election Day by replacing their outdated equipment.

There are other reasons jurisdictions will want to purchase new voting equipment in the next few years. Most importantly, the independent and bipartisan Election Assistance Commission recently approved the most significant update to federal voting technology standards since 2005. These standards, called the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines, set baseline requirements for voting machine cybersecurity, accessibility, and usability that vendors agree to meet, and that most states require for any voting machine in use. Adherence can help election officials assure voters that their technology has been certified by independent and authoritative standards and can reassure a public that is increasingly exposed to false conspiracy theories about the security of our nation’s voting equipment.

Outdated Voting Equipment

There are several categories of machines that ought to be replaced.

Direct recording electronic voting machines

Direct recording electronic voting machines use push buttons, dials, or touchscreens to record votes. This equipment has faced criticism from security experts because it records votes directly into computer memory and, in the case of some equipment, lacks voter-verified paper audit trail printers.

Significant progress has been made in recent years toward phasing out the direct recording electronic voting machines. In 2016, 22.4 percent of registered voters lived in jurisdictions using those direct recording machines that did not produce a paper backup. This year, we anticipate this figure to be closer to 1.4 percent.1

Our 2022 analysis found that six states still used paperless equipment. By November, many of those machines will be replaced. Indiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee have all passed legislation that requires localities to update or replace their paperless machines with systems that produce a paper record of every vote. An Indiana bill requires all counties using direct recording electronic voting machines to be equipped with voter-verified paper audit trail printers by 2024. In 2022, Mississippi passed legislation requiring the use of voting systems that produce voter-verifiable paper ballots starting in 2024; that same year, a Tennessee law required all direct recording electronic voting machines used in the state to be equipped with voter-verified paper audit trail printers by 2024. Kentucky has also replaced its remaining DREs.

Texas counties have until 2026 to replace their paperless direct recording electronic voting machines, though several counties have already made progress toward this goal. Louisiana, which has used paperless direct recording electronic voting machines statewide since 2006, intends to replace its voting machines with a paper-based system; however, this may not take place before the November 2024 presidential election.

The number of states with jurisdictions using the direct recording machines with voter-verified paper audit trail printers has decreased as well. The Brennan Center’s first analysis in 2014 found that jurisdictions in 22 states used some form of the direct recording machines as the primary polling place equipment. Ten years later, that number has shrunk to eight.

Machines that are reaching the end of their life cycle

Just like phones and computers, voting machines become obsolete with age. Twenty-first century electronic voting machines are considered to have a lifespan of 10 to 20 years, with most systems leaning closer to 10. Election officials often have difficulty finding machines that can run on outdated software, and, according to cybersecurity expert Jeremy Epstein, “From a security perspective, old software is riskier, because new methods of attack are constantly being developed, and older software is likely to be vulnerable.”

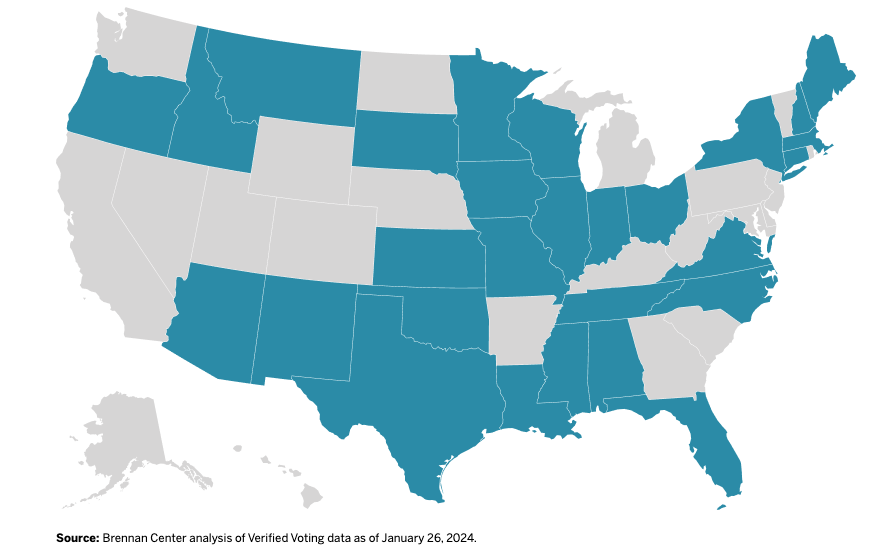

In November 2024, we expect that nearly 44.6 million registered voters will live in jurisdictions using principal voting equipment that was first fielded more than 10 years ago.2 This number has slightly increased since 2022 because states and territories that replaced their voting equipment as recently as 2014 are now using equipment that may be at or beyond its lifespan. We expect these to be among the first states to want to purchase new equipment that complies with the new federal voting system guidelines.

States with Jurisdictions Using Principal Voting Equipment That Is 10 Years Old or Older

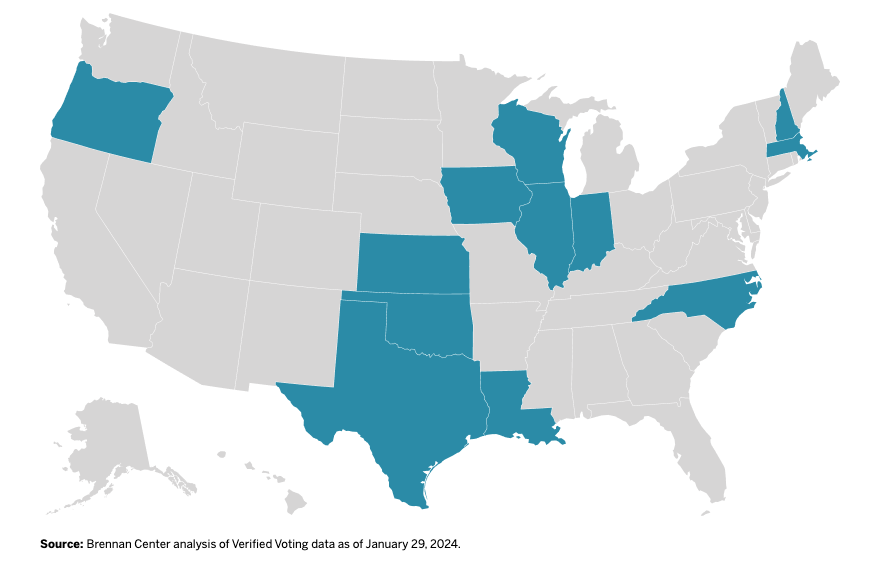

Voting machines may also pose issues for election officials if the equipment is discontinued. Replacement parts and technicians become difficult to find for equipment that is no longer being manufactured. One election official expressed that he felt “lucky to be able to get spare parts” for discontinued systems in his jurisdiction. In November 2024, about 10 million registered voters will live in jurisdictions using principal voting equipment that is no longer manufactured. This number has decreased dramatically from 21 million registered voters in 2022.

States With Jurisdictions Using Discontinued Principal Voting Equipment

The Help America Vote Act requires that individuals with disabilities can access voting systems that allow them to vote privately and independently. In 2024, more than 23 million voters will live in jurisdictions that use assistive voting equipment that is no longer being manufactured.

Cost of Replacing Outdated Voting Machines

While federal funding of elections since 2016 has spurred progress toward the goal of securing our elections in recent years, that funding has been irregular, dwindling, and insufficient to keep voting technology up to date in every state. Without additional, reliable funding, American election infrastructure will be more vulnerable to malfunction and attacks, during a time when public confidence in elections is particularly essential.

To replace a direct recording electronic voting machine without voter-verified paper audit trail printers, jurisdictions can use hand-marked paper ballots and optical scanners, which scan and tabulate votes; ballot marking devices, which allow voters to mark their ballots on a computerized interface with visual or audio prompts, should be available for voters with disabilities. Replacing the direct recording electronic voting machines without voter-verified paper audit trail printers in the remaining jurisdictions will cost approximately $37.5 million.3

Voting machines will continue to age out in the coming years. Election officials typically struggle to plan their budgets ahead of time because no sustained federal funding to administer elections exists; financial support is doled out sparingly and often only in desperate situations. We estimate that the cost of replacing all voting equipment used by in-person voters, including principal polling place equipment and assistive voting devices, first fielded in 2014 or earlier is $203 million.4 The cost of replacing all voting equipment used by in-person voters that is no longer being manufactured is nearly $150 million.5

In the next five years, tens of thousands more voting machines will have been in the field for nearly a decade. As discussed above, with new federal standards for security, and new systems that meet those standards likely to come on the market in that time, jurisdictions with this outdated equipment are likely to be particularly anxious to do so, if they have the funds. These estimates do not include other maintenance costs for security patches, software upgrades, and licensing fees. Every state in the country also uses mail ballot tabulating equipment, and replacing these machines could cost an additional tens of millions of dollars.

This analysis was originally published by the Brennan Center here.

-

1. See Verified Voting, The Verifier — Election Day Equipment — November 2024, https://verifiedvoting.org/verifier/ (last accessed Jan 29, 2024) (The data in this analysis reflects Verified Voting’s research as of this publication and includes confirmed data and/or explicit jurisdictional intention to upgrade equipment, which may not be reflected on The Verifier. Jurisdictions will likely continue to make changes to their voting equipment before the November 2024 presidential election.)

-

2. See Verified Voting, supra note 1. (The data in this analysis reflects Verified Voting’s research as of this publication and includes confirmed data and/or explicit jurisdictional intention to upgrade equipment, which may not be reflected on The Verifier. Jurisdictions will likely continue to make changes to their voting equipment before the November presidential election. Some of the jurisdictions included in this figure are all mail ballot jurisdictions, meaning every voter is mailed a ballot and most voters do not vote in person using voting machines.)

-

3.To reach this estimate, we relied on Verified Voting data from January 2024. This estimate assumes that precinct count optical scan machines cost $5,000 each and ballot-marking devices cost $3,500 each. We multiplied each of these costs by 4,407, the number of precincts that still use direct recording electronic voting machines without a voter-verified paper audit trail for all voters on Election Day. This amounts to $37,459,500. See generally State of Michigan Central Procurement Services, Revisions for the Contract Between Dominion Voting Systems and the State of Michigan (2017), https://www.michigan.gov/documents/localgov/7700117_555468_7.pdf; see also Dominion Voting Systems, State of Ohio Pricing (2021), https://procure.ohio.gov/pdf/OT902619_Dominion%202021%20Price%20Sheet.pdf; State of Nebraska, Service Contract Award (2020), https://statecontracts.nebraska.gov/Search/ViewDocument?D=7XEyLqmfbfEfFzaF9z49Gw%3D%3D; Dominion Voting Systems, Standard Agreement Form for Professional Services (2019), available at https://verifiedvoting.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/AK_2019-dominion-voting-systems-contract.pdf.

-

4. To reach this estimate, we relied on Verified Voting data from January 2024. We used $5,000 as an estimate for our per-machine replacement cost. We multiplied $5,000 by 40,626, the number of instances in which a precinct uses principal or assistive voting machines on Election Day that were fielded in 2014 or earlier. This amounts to $203,130,000. See generally contracts cited supra note 3.

-

5. To reach this estimate, we relied on Verified Voting data from January 2024. We used $5,000 as an estimate for our per-machine replacement cost. We multiplied $5,000 by 29,804, the number of instances in which a precinct uses principal or assistive voting machines on Election Day that are no longer being manufactured. This amounts to $149,020,000. See generally contracts cited supra note 3.