On March 25, the Trump Administration issued an executive order (EO), “Preserving and Protecting the Integrity of American Elections.” Despite its title, the EO does not protect the integrity of American elections, something that is a nonpartisan priority for all voters, regardless of party.

For the record, an EO is not the same as a law passed by Congress, and this one conflicts with some existing laws. As written, the EO upends the constitutional framework that ensures states administer elections, creating unnecessary uncertainty for election officials and potentially confusion for voters. For these and other reasons, the EO has already been challenged in court. Several organizations have filed lawsuits, including The Campaign Legal Center and the State Democracy Defenders Fund, noting that the president does not have the authority to dictate election rules. In addition, a coalition of civil rights groups also sent this letter to the Election Assistance Commission (EAC), highlighting a number of legal and regulatory issues with implementing the order—more on that below.

The EO includes some sections with implications for election technology. Here are some specifics:

Paper Ballots/Paper Records are mentioned in Section 1, where the EO says that for elections to be worthy of the public’s trust, voting methods must “produce a voter-verifiable paper record allowing voters to efficiently check their votes to protect against fraud or mistake.” Verified Voting has championed paper ballots for more than 20 years, so we have been tracking this on the Verifier: today, paper ballots and paper records are already in use in every state except Louisiana. Voters use a patchwork of different voting systems depending on where they live, because elections are run by the states, and rules vary.1 For more than two decades, movement toward ensuring all voters can review their choices on a physical ballot has been widespread and consistent. That said, not all paper-based voting systems are the same, and the details matter.

Barcodes and QR Codes are mentioned in Section 4 of the EO: “Improving the Election Assistance Commission” (EAC), seeks a change in the guidelines, known as the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG), against which voting systems are tested and certified by the EAC. The goal of the proposed change is to prohibit [decertify] voting systems, primarily certain ballot marking devices (BMDs), that use barcodes or QR codes to encode voter choices.

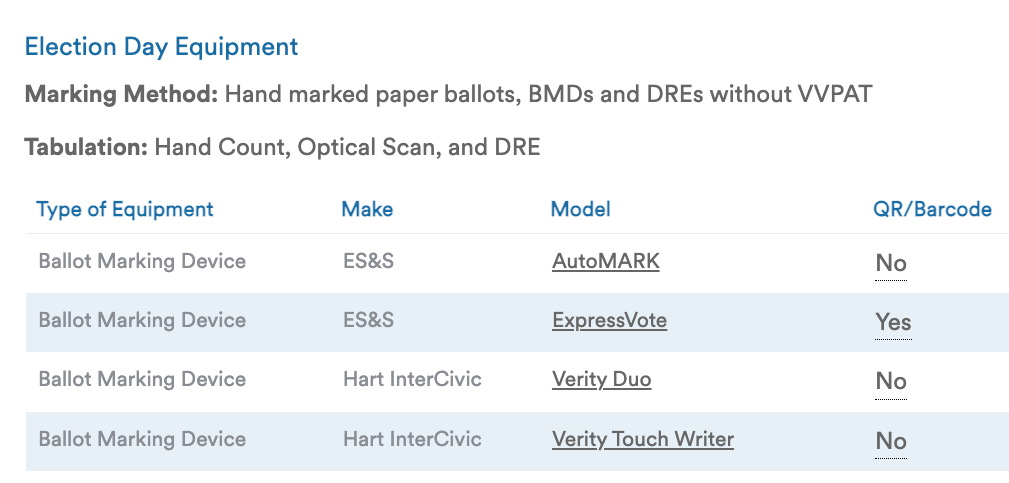

BMDs provide an accessible voting option for voters. It is a federal requirement to provide at least one accessible system per polling place. The BMD presents the ballot to a voter through an electronic interface, allowing the voter to make selections, and then produces a paper record printout for the voter to check before casting.2 On some models, that paper record printout includes encoding of vote choices in a barcode or QR code along with a summary list of vote choices. Other models produce a paper record that is only a summary list of the voter’s choices in plain text, while still other BMDs generate printouts similar to a hand-marked paper ballot (fill in the oval), which do not encode votes.

To be clear, bar/QR encoding of votes is neither necessary nor desirable because voters can’t interpret what’s in the encoding, and votes should be counted from human-readable text that voters can verify (for a deep dive, read this piece by Prof. Andrew Appel, who has written extensively about the use of codes on ballots). Encoding is not needed to count votes if the system is designed to count either using Optical Character Recognition (OCR), that is, reading the selections —that voters can verify—from the plain text, or by detecting the filled-in ovals.

Currently, 1,954 counties spread across 40 states use voting machines that encode votes in QR or barcodes (though the use of non-encoding systems is growing). In some places, these machines are used to provide accessible voting for voters with disabilities, where most voters manually mark a paper ballot. In other jurisdictions, BMDs are in use for all voters. To find out if your jurisdiction uses machines that print barcodes or QR codes to encode votes, visit the Verifier, click on your state and county, and scroll down to the voting equipment table—we’ve added a column showing if a certain system encodes votes.

It’s important to understand the paper ballot and encoding provisions of the EO in context. The order says the EAC must bring about these new requirements by changing the guidelines—known as the Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG)—to which federal testing and certification is carried out. Updating these standards involves layers of critical stakeholder input and public comment periods so that you and others can weigh in. That takes significantly more time than the order contemplates, even if the Administration had the authority to direct the EAC in this way (it does not).

A key word here is “voluntary”. Adherence to the VVSG is voluntary—meaning it is left up to the states to decide if they require their voting systems to be certified federally at all, and if so, to the most current version of the VVSG. As of the time of the most recent update to the VVSG (Feb. 2021), “11 states and Washington, D.C. require full EAC certification of voting equipment in statute or rule” according to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL).

Also worth noting: right now, no voting systems are yet certified to the most current standards, though there are a few in the testing phase. Even so, a number of states have already moved away from encoding on ballots with more likely to follow, making it clear that a confusing executive order with no funding support is not necessarily the best way to get things done.

The original version of this blog was published on April 9, 2025 and was updated on May 21, 2025 to clarify and include more information about voting systems that encode votes.

- Currently, 68.4% of voters live in jurisdictions using hand marked paper ballots for most voters, 26.5% of voters live in jurisdictions using ballot marking devices (BMD) for all voters, and 5.1% live in jurisdictions using direct recording electronic (DRE) machines for all voters. https://verifiedvoting.org/verifier [↩]

- Bar/QR codes are sometimes employed on paper ballots to tell a scanner how to read a paper ballot and may not encode votes. Those are distinct from encoding of voter selections. [↩]