A joint analysis from the Brennan Center and Verified Voting finds replacing aging voting equipment will cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

Voting Machines at Risk in 2022

by Turquoise Baker, Megan Maier, Lawrence Norden, and Warren Stewart

Between 2014 and 2020, the Brennan Center released a series of analyses detailing the problem of aging voting equipment in the United States. Those analyses relied significantly on data provided by Verified Voting. Today, our organizations update those analyses with a look at the state of the nation’s voting systems ahead of the November 2022 midterm elections.

The Brennan Center’s first overview of voting systems in the United States, published in 2014, found that 43 states relied on machines that were past or near the end of their expected lifespans. Fourteen states used at least some machines that were no longer manufactured and difficult to repair. Outdated machines suffer frequent breakdowns and create long lines at polling places. They are also more susceptible to error and fraud, risking public confidence in elections.

Since that report, the nation has made significant progress toward replacing its most insecure systems. In 2012, for example, the majority of Election Day voters in some or all counties in 16 states voted on direct recording electronic (DRE) voting machines that do not produce a voter-verified paper audit trail (VVPAT). Security experts have long identified DREs as a unique security risk. By 2022, jurisdictions in only six states (Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, Tennessee, and Texas) relied on those machines as their principal voting equipment — that is, the technology used by most voters on Election Day in an election jurisdiction.

Outdated voting systems, however, remain a problem. Machines are aging past their projected life cycle without being replaced, leaving jurisdictions with systems that are significantly more than a decade old. Many of these systems are no longer manufactured, which can make it difficult or impossible to find replacement parts.

By the Numbers: Outdated Voting Equipment

Like any computerized system, voting machines age into obsolescence. For electronic voting machines purchased since 2000, experts agree that the expected lifespan for the core components is between 10 and 20 years. For most systems, however, it is probably closer to 10 than 20. Furthermore, according to cybersecurity expert Jeremy Epstein, “from a security perspective, old software is riskier, because new methods of attack are constantly being developed, and older software is likely to be vulnerable.”

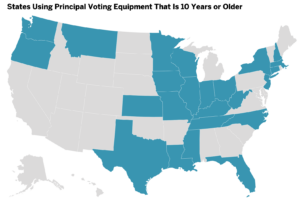

Today, 24 states, home to over 41 million registered voters, use machines first fielded more than a decade ago as their principal voting equipment. While jurisdictions in many states have replaced older voting machines in the last eight years, the need to replace equipment as it ages continues.

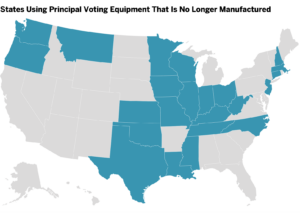

The age of equipment is just one way to estimate how soon jurisdictions will need to replace it. Another important gauge is whether that equipment is still being manufactured. Many election officials using discontinued systems have expressed concerns to the Brennan Center about their ability to find replacement parts and technicians to service these machines.

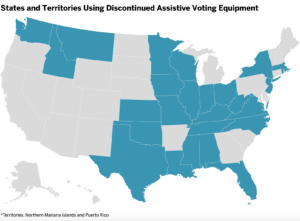

Currently, the principal voting equipment in 23 states with nearly 21 million registered voters is no longer manufactured. And approximately 40 million voters live in 26 states and two territories relying on assistive voting equipment — systems that are required under the Help America Vote Act to ensure that individuals with disabilities can vote privately and independently — that has been discontinued. This equipment poses a serious problem for election officials, since old and discontinued machines can be particularly difficult to maintain. One election official felt “lucky to be able to get spare parts” for the machines that had been discontinued in his jurisdiction.

Of particular concern are jurisdictions that still use DRE voting machines. These machines, which may or may not produce a VVPAT, generally require a voter to use a touch-screen monitor to vote. In recent years, a number of these models have “flipped” votes, with the touch screen incorrectly registering voters’ choices due to calibration errors associated with aging hardware. That, in turn, has led to viral videos and conspiracy theories of machines “stealing votes.”

While the number of jurisdictions using DREs has fallen dramatically in recent years, nearly 26 million registered voters in 16 states live in jurisdictions that still use DREs for some or all voters as of February 2022. And of those, more than 13 million registered voters live in six states (Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Jersey, Tennessee, and Texas) that use DREs without VVPAT as their principal polling place equipment for some or all voters.1

Four of these states have started to address their DRE vulnerability. Louisiana passed a bill last year requiring new voting systems to “produce an auditable voter-verified paper record.” The state is in the process of selecting new voting machines. A new Texas law requires the state to phase out DREs by September 1, 2026, although curbside voters may still vote on DREs without VVPAT. Indiana passed a bill in January requiring jurisdictions with DREs to add VVPAT printers by 2024. New Jersey has required VVPAT since 2009. Despite that deadline, many counties continue to use paperless systems, purportedly because of a lack of funding to replace them.

New voting machines that produce a paper ballot for each vote cast make it possible for election officials to conduct post-election audits. Approximately half of all states and the District of Columbia conduct post-election audits, which require a review of paper ballots to check the accuracy of the votes cast. With partisan actors fueled by the Big Lie conducting partisan reviews that undermine confidence in our elections, it is becoming increasingly important for qualified election officials to conduct legitimate audits of their own.

The Cost of Replacing Outdated Voting Machines

Replacing the outdated equipment listed in this report will cost several hundred million dollars over the next few years. Failure to do so will leave our election systems vulnerable to breakdowns, error, and attack, and further threaten public confidence.

States can replace a DRE without VVPAT with a ballot-marking device (BMD), which allows voters to vote on a computerized interface by interacting with visual or audio prompts, and a precinct count optical scanner, which scans and tabulates votes. We estimate that the cost of replacing the remaining DREs without VVPAT with BMDs and precinct count optical scanners will be about $105 million.2

DREs, however, make up just a fraction of the outdated equipment that has reached the end of its life cycle. We estimate that the cost of replacing principal polling place equipment and equipment for assistive voting that was first fielded in 2010 or earlier is over $350 million.3

Even with full replacement of these outdated systems, other machines and systems will continue to age out over the next decade. One of the challenges for election jurisdictions around the country is that financial support often comes only when the situation becomes dire (and sometimes not even then). There has been no sustained federal funding to administer elections or to maintain the critical infrastructure that supports those elections.

In the next five years, tens of thousands of voting machines will have been in the field for nearly a decade. We estimate that the cost of replacing equipment first fielded between 2010 and 2016 will be more than $230 million, for a total cost of more than $580 million for replacing outdated voting equipment over the next five years.4 These estimates do not include the cost of regular security maintenance for things like security patches, software upgrades, and licensing fees, which can be quite expensive, or the cost of replacing outdated mail ballot tabulating equipment, which is used in every state in the country. These scanners can cost anywhere between $50,000 and $100,000 each, and the total cost for replacing outdated mail equipment could easily cost many tens of millions of dollars more.

The price tag as we get further out in time will only grow. The Center for Secure and Modern Elections has estimated that the full cost of replacing outdated voting machines over the next decade will amount to $1.8 billion.

This analysis was originally published by the Brennan Center here.

- Registered voters in Kentucky and Oklahoma use DREs without VVPAT as accessible voting machines. [↩]

- To reach this estimate, we relied on Verified Voting data from February 2022. This estimate assumes that precinct count optical scan machines cost $5,000 each and ballot-marking devices cost $3,500 each. We multiplied each of these costs by 12,374, the number of precincts that use DREs without a voter-verified paper audit trail for all voters. This amounts to $105,179,000. See State of Michigan Central Procurement Services, Revisions for the Contract Between Dominion Voting Systems and the State of Michigan, 2017, https://www.michigan.gov/documents/localgov/7700117_555468_7.pdf; and Dominion Voting Systems, “State of Ohio Pricing, ITB:0T902619,” accessed June 24, 2021, 22–23, https://procure.ohio.gov/pdf/OT902619_Dominion%202021%20Price%20Sheet.pdf. [↩]

- To reach this estimate, we relied on Verified Voting data from February 2022. We used $5,000 as an estimate for our per-machine replacement cost. We multiplied $5,000 by 70,271, the number of instances in which a precinct uses either principal or assistive voting machines on Election Day that were fielded in 2010 or earlier. This amounts to $351,335,000. See State of Michigan Central Procurement Services, Revisions for the Contract Between Dominion Voting Systems and the State of Michigan. [↩]

- To reach this estimate, we relied on Verified Voting data from February 2022. We used $5,000 as an estimate for our per-machine replacement cost. We multiplied $5,000 by 116,787, the number of instances in which a precinct uses either principal or assistive voting machines on Election Day that were fielded in 2016 or earlier. This amounts to $583,935,000. From this figure, we subtracted the replacement cost for principal and assistive voting machines used on Election Day that were fielded in 2010 or earlier ($351,335,000). This amounts to $232,600,000. See State of Michigan Central Procurement Services, Revisions for the Contract Between Dominion Voting Systems and the State of Michigan. [↩]